New York City is drowning in killer intersections and too-wide streets. Areas like Midtown are especially impacted by NYC’s unrelenting car culture. Congestion pricing is key but not the only change necessary. Reimagining streets may be the most important way forward.

After decades of car-centered planning, news outlets recently reported that NYC has won the unenviable title of the world’s worst traffic.

A street network is like the root system at the base of how any society functions. Unfortunately, the motor vehicle has dominated urban development for decades, leading to devastating results for our cities and our lives, including struggling local businesses, an unhealthy and increasingly isolated population, increasingly hostile streets, and a scary number of fatal car crashes every year.

We do not understand, nor do we have data evaluating, the way our streets have supported social and commercial life for the past 70 years, only how they support cars. As a result, our cities (and business districts in particular) have become totally saturated with traffic and shaped by the wishes of drivers.

Midtown is at a breaking point and its survival hinges on what we choose to do next with its streets. For tech businesses and a growing number of other office tenants, Midtown has lost popularity to older, more fine-grained neighborhoods. This is not surprising since, at the end of the day, office workers and businessmen are people like everyone else, and people gravitate to social life, amenities, and vibrant surroundings. What's more, at the end of the workday, much of Midtown is dead because it offers little to people outside of work space and car space.

We need to entirely redefine our approach to how streets and sidewalks function in the heart of NYC so that we can transform them from mere conduits for traffic into settings for thriving social and commercial activity where public life thrives. Now is the time to bring Midtown back to life by revitalizing its streets and making them more appealing to all.

Congestion Pricing is Good, But Not the Only Way to Reduce Traffic

While we support congestion pricing, we believe that re-designing our streets can have an even bigger impact.

The central, historical, New York City districts need to be completely reinvented. In their current form, they do not live up to their potential or support the kind of activity that the downtowns of one of the world's greatest cities should. New York's most central areas have become dominated by cars and every behavior apart from driving has (literally) been pushed into the margins.

The city knows it has a traffic problem. To catalyze a much-needed transformation, dramatic traffic reduction strategies are starting to be implemented, such as the congestion pricing that was going to be launched in Midtown this past summer, where cars would have been charged $15 or more for entering Midtown below 60th street, right around the entrance of Central Park. This was expected to result in 100,000 fewer vehicles entering the area every day. It would have been a landmark opportunity to revitalize the heart of NYC and take this key area back from cars. The problem is it didn't happen. The congestion pricing plan has been put on hold in service of the deeply ingrained commitment to cars that New York can't claw itself out of and no progress has been made yet.

We hope that congestion pricing will be implemented because the heart of a city is no place to fill with cars. However, whether it moves forward or not, we can still make driving less appealing through design, by shifting our streets' focus away from catering to cars and toward catering to pedestrians and businesses. Improving and widening sidewalks is also a powerful traffic reduction strategy. Doing so would expand the area we devote to pedestrian life, concurrently reducing the space for cars. The result would be a city for all, not just for drivers. We would join many other cities around the world that are improving social and economic life by rehumanizing our streets.

A Closer Look at Midtown Manhattan

In a Midtown saturated with motor vehicles on both its main avenues and side streets, making your way around is no thrill. Much of the area has become an isolated desert after work hours are over, leading New York to lose its allure as a major global city. Streets have been "improved" by traffic engineers over time to get more and more vehicles through at the expense of sidewalk width and vibrancy.

Some of the most central streets in Midtown have 5+ lanes! That is a highway sized street in the center of the city... This is absurd and unheard of. We should be embarrassed. City streets should be places where people connect with each other and businesses thrive, not drag strips for cars to speed along as smoothly as possible. To treat them as such is to treat them with disrespect and a lack of understanding about what a street's role in a city should be.

Killer Intersections

Almost every intersection in Midtown is what we call a "Killer Intersection" – an intersection that is not only dangerous but that kills social and commercial life in its vicinity. In the most beautiful and beloved cities of the world, intersections are vibrant destinations because the corners are treated as prime spots for the best restaurants, cafés, and landmarks. In Midtown, intersections are dominated by cars and nothing good happens on the corners.

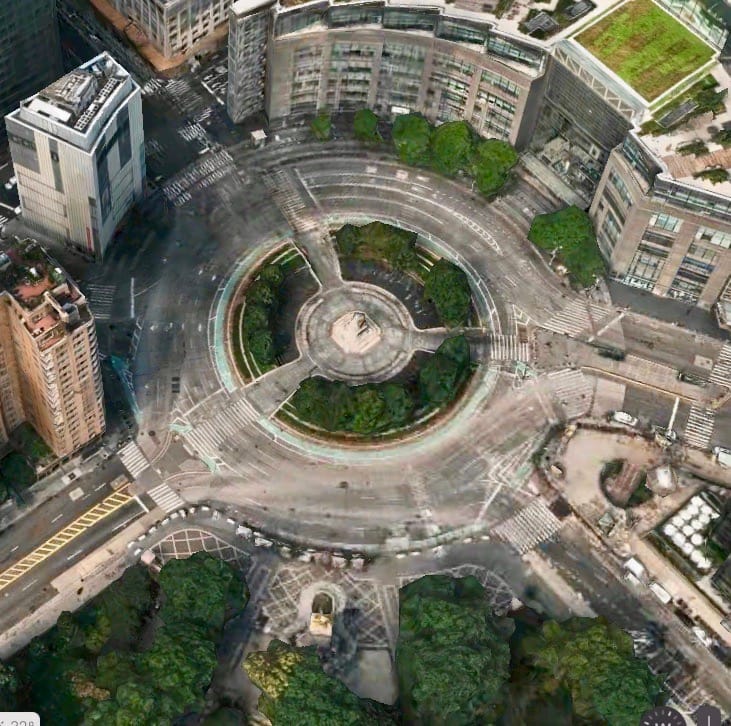

Central Park Intersections

Even our most iconic, greenest destination is being strangled by traffic. Central Park is a great example of how far we've fallen. The most prominent destination in Manhattan is wrapped in highway-sized streets and punctuated by Killer Intersections. Despite being in the heart of the city, the park feels isolated and disconnected.

Instead of connecting Midtown to Uptown, drawing people in and serving as gateways into our most precious public spaces and neighborhoods such as The Upper West Side, Lincoln Center, The Upper East Side, and most importantly Central Park, the streets and intersections here act as barriers to them, dividing Manhattan down the middle with walls of traffic. They are just a couple of the numerous terrible intersections at key locations in New York.

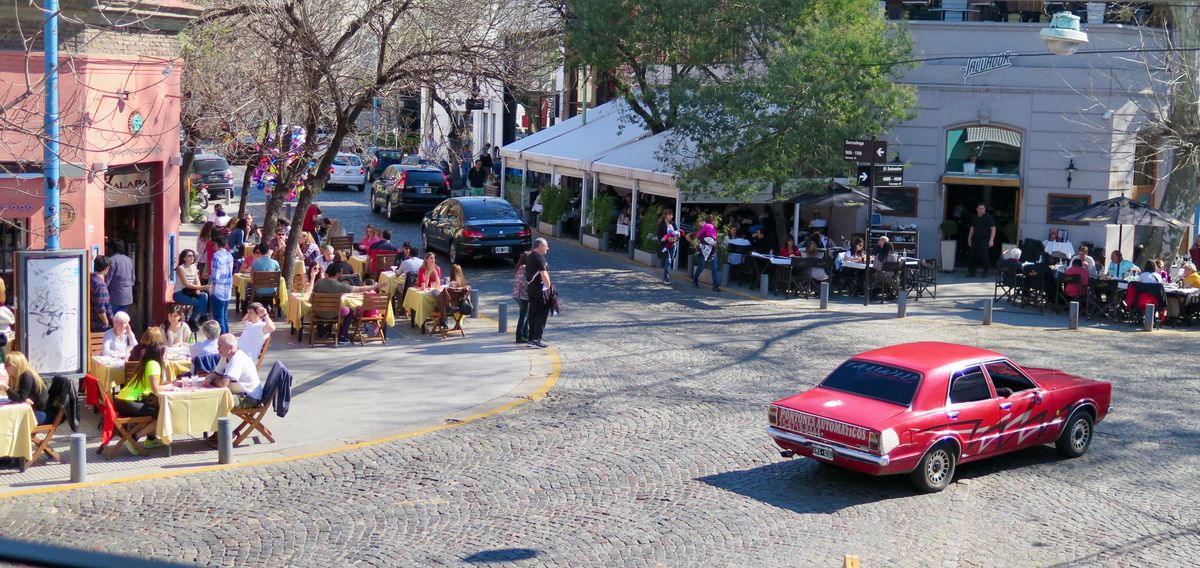

Columbus Circle on The Western Corner:

Columbus Circle

Grand Army Plaza on the Eastern Corner:

Fifth Avenue - Grand Army Plaza and 58-60th Street

NYC's Crosstown Streets

The avenues are in dire need of improvement but NYC's crosstown streets are also in trouble. Virtually all Midtown streets are "stacked" with traffic, with three lanes or more being pushed through each avenue, making intersections oversized and chaotic. The corners are dominated by vehicles instead of pedestrian or commercial activity. Turn lanes often increase the traffic bulk, with additional wait times added that increase car capacity despite the impact and threat to pedestrians.

For example, at Rockefeller Center, intersections have been "improved" to get more vehicular throughput by stacking three lanes of vehicles across and adding turn lanes going into crosstown streets. Cars dominate the corner here so that any sense of what is going on mid-block at this important location, instead of being easy to see and drawing in foot traffic, is out-of-sight and out-of-mind.

With all the cars visually dominating corners (a key viewpoint into crosstown streets) interesting destinations deeper down the block are hidden from view or unrecognizable. The intersections in Midtown don't serve pedestrians or businesses. They serve no one but cars.

Furthermore, bike lanes are on many of these streets, often cutting right between outdoor dining areas and sidewalks, creating a dangerous and unpleasant situation. This positions outdoor dining spaces as an obstacle to mobility when they should instead be welcoming and vibrant places integrated with and enhancing sidewalk life.

How did we get here?

NYC's path to car-centrism started in the post-war era. That is when the car began to reign supreme everywhere, destroying nearly everything in its path. Massive highways plowed through inner cities, mostly poor neighborhoods, thus separating the wealthier communities from the poorer ones. Schools were moved out of communities as school districts consolidated into large regional schools where the only way to reach them was by driving, thus robbing young people of independence and a connection to the broader community. Main streets became dominated by cars and chain stores instead of pedestrians and local businesses. The result has been a breakdown of our social and economic fabric that has left us reeling. We now have to reckon with the results of these changes and work to recover from decades of destruction. It will not be easy, but it is necessary if we want to save our cities.

As we look to the past and examine what happened to NYC, we have increasingly realized that we have a unique perspective on the situation. Our work started in the early 1970's when there was an enormous building boom of office centers in contemporary, international architecture styles. They were being developed alongside a totally auto-centric system of expansive roads and highways to provide access to them, leaving people and the things people enjoy out of the equation.

Transit was barely handling this transformation. We worked on town centers in the 1980's to address the problem with innovative actions done in small towns all around New Jersey and a few on Long Island. For the past 40 years, as the Placemaking movement, we have been working on creating great car-free public spaces in cities that are drowning in traffic.

State and local transportation agencies today are painfully aware of the car-centric situation and are being challenged to reconstitute. Bike movements and other transportation alternatives are growing. Everyone is struggling to survive and thrive under the weight of the car-centrism we've wrapped ourselves up in. The city itself is struggling to make it out alive.

A Plan for the Future

We can't go on like this. The soul of New York, what once made it a place worth being in, is being preyed on by car culture and soon there may be nothing left to salvage. We need to turn everything upside down to get right side up again. The plan to save the city will start by changing our focus from cars to people – shifting our priority from designing for cars and traffic to designing for people and social life.

Our plan to revitalize Midtown offers an assessment of what has gone wrong and what we need to focus on to make progress. It sets out a proposal for how we can move forward from NYC's current state of continuing decline:

Midtown is plagued by a variety of problems that lead to a deeply underperforming urban core. Assets aren't highlighted, cars are inescapable, pedestrians and business activity are pushed to the margins, public plazas are badly designed, and as a whole, there is very little effort made to create an enjoyable experience for anyone except drivers.

Let's take a closer look.

1) Landmarks aren't highlighted

Important destinations in Midtown are not highlighted, but instead drowning in traffic. For example, Radio City Music Hall, one of NYC's biggest landmarks, is shoved into a second rate setting along Avenue of the Americas. It is pressed right up against traffic with a narrow sidewalk void of activity and has nothing of interest happening around it to signal its importance to the city and its history. One of the most prominent landmarks in the city deserves a presence more akin to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. There should be a square here, a wider sidewalk at least, and features around that celebrate it and elevate it to the status it deserves.

The other Rockefeller Center buildings have fountains and sculptures and gardens and squares around that ornament them and emphasize their importance. This is what iconic buildings deserve – surroundings that highlight them and invite people to come marvel at them, rather than surroundings that minimize their star power. Creating a "Rockefeller Center" style presence for Radio City and remaking the space around it into vibrant and activated squares would be transformative. Other great landmarks and destinations in Midtown deserve the same treatment too.

On a similar note, public places are missing gateways. Observe how NYC's main avenues just dead-end into Central Park. As Manhattan's most important and biggest public space, Central Park deserves a worthy entranceway like other such places around the world have, welcoming people in and dignifying the space. There is no such entranceway here, only enormous, chaotic, deeply unpleasant intersections.

59th street, between Central Park and Midtown, is more like a wall than the entrance into our most prized and well-known park.

Avenue of the Americas and Seventh Avenue Meeting 59th

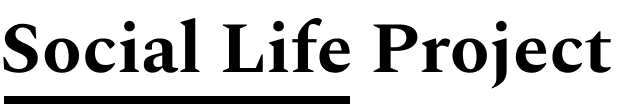

Here are some examples of the gateways that other great cities have at the entrances of their landmark spaces. Why does Central Park have nothing of the sort when it is one of the most famous destinations in the world?

Barcelona and Amsterdam

What is also striking is how few attractions there are in the southern end of Central Park – in other words, the part that is closest to the traffic wall. The entire stretch could become much stronger as a destination but it feels like the proximity to multiple lanes of traffic and chaos is hindering this. If the park's southern entrance was better connected to the foot traffic flowing in from Midtown, it would naturally become a more dynamic place.

The area around the lake on the southeast side is a beautiful park-like oasis that could become more like the lake in Brooklyn Botanic Gardens. The rest could become much more active and interesting, mirroring the renowned Pleasure Gardens of the early 18th Century. Tivoli Gardens in Copenhagen is one of the few remaining from that era and still a deeply beloved destination that never fails to entertain.

Copenhagen's Tivoli Gardens

2) Not enough food or refreshment

There aren't enough enjoyable places to stop for refreshment along Midtown's central streets. As most cities around the world will show, central streets need to have plentiful options for refreshment along their length because food and drink is what draws people in and mobilizes foot traffic more than anything else. What Midtown offers is either high end cafes inside of buildings or small standalone food trucks that allow sidewalks to stay narrow and streets wide. Why is it so hard to find pleasant seating to eat what you buy from these vendors?

Eating isn't just something to do on the go, it's something to sit and enjoy. Often, it's a social experience. There must therefore be a variety of places where people can stop and consume in a pleasant environment. If the experience of eating, drinking and lingering isn't enjoyable, much fewer people will engage in it. This isn't good for business or social life.

3) Unused and unusable public plazas

The places that are available for people to sit and rest in Midtown are usually dull, generic, corporate plazas. The color gray and sharp edges abound. Too many of these plazas are built in a way that simply centers office buildings rather than creating a pleasant experience for the public. They are mostly empty space punctuated by barely usable seating and plantings. This isn't a true plaza, but a mockery of one.

A good square should give a view of "the City at Eye level" and be a place where there are active ground floors with things to see and do, and a people-centered design which prioritizes the user experience. There should be things to enjoy there like cafés and games and play areas for children. Otherwise why would people spend time there? While technically public, Midtown plazas offer little actual appeal for public use. In fact, they look purposefully designed to not be used or enjoyed.

Avenue of Americas Plazas

One of numerous examples of a barely usable plaza is the Apple Store plaza. This is a sad example of a new public space that is just another designer-led, dysfunctional and even dangerous space (note the chains to keep people from tripping into the odd water features). The seating isn't comfortable, the atmosphere isn't welcoming. Who is this plaza designed for?

So much of Midtown is not designed for people. You can see how every decision was made to cater to cars or office buildings and everything else is deprioritized or even made to feel unwelcome. But the Big Apple is not a city only for drivers and offices. It is a city that is home to 8 million people, over half of which who do not have a car. It is a home to children, elderly people, people with disabilities, and the universal human desire to relax and enjoy oneself. To design the heart of a city to only support driving and getting into and out of the office is absurd. Our streets need to support every kind of life the city plays home to and NYC's Midtown is currently far from getting this right.

The Big Opportunity for NYC: Start with the Sidewalks and Intersections

Beginning 50 years ago, we were part of a concerted campaign of public space activations and transformations led by both the public and private sectors that transformed moribund and even dangerous places in Midtown into some of the best public spaces in the world. In the 1990s, we started using the term "Placemaking" to describe public space transformation that was driven by the people in communities.

What we've found that is especially notable about great streets in cities around the world is a simple concept: when you have wide enough sidewalks (say 30 feet) where people can stroll, shop, and eat in cafés, you get people (surprise) strolling, shopping, and eating in cafés. Sidewalk design matters. Designing for people attracts people and designing for cars attracts cars. Even the former chairman of Volkswagen understands this, seen below quoting us.

Not only should sidewalks be wide enough to support all manner of social and commercial activity, they should also be interesting places to be. We call great sidewalks with something happening on both sides of the pedestrian walkway "double-loaded." In other words, the sidewalk is animated in two layers – by what's at the building base as well as what is going on along the curb. On streets like the Avenue of the Americas, curbside cafés, seating, and retail can animate a sidewalk.

You can orchestrate an alignment between what's happening in the private and public realms by putting pedestrian space where it has the most potential to activate life inside buildings, which can be done when those buildings are "turned inside out." This means that what normally happens inside spills outside, such as seating, displays of goods, and retail activity. It makes the sidewalk much more interesting and attracts foot traffic.

The other important lesson we have learned about how to revitalize cities relates to how major public spaces become destinations and, thereby, extensions of street and sidewalk life. Times Square is our best example of this concept in Midtown, demonstrating that it's not only the space, but also the connections to it that matter if your goal is to revitalize an entire district. Isolating destinations by cutting them off from their surroundings with wide, busy streets destroys the positive impact they are able to have on the broader community and the harmonious continuity of public space that revitalizes the urban fabric.

A grid of streets is not enough at the core of a city. Streets move us around but destinations are where we stop and actually experience and enjoy the city. The streets need to lead us to destinations we want to end up at. Without destinations like vibrant squares, parks, landmarks, and plazas, or with destinations too few and far apart as is the case in Midtown, we are constantly moving without encountering opportunities to rest, experience, and recharge.

If we want to make NYC's downtown areas full of vitality and appeal, we need to stop designing them to be conduits for the smooth passage of cars and start designing them to be full of interesting and vibrant destinations for people. Too much has been sacrificed to make New York easy to drive through, namely everything that makes it interesting and pleasant to be in. This cannot continue or we will lose everything we hold dear.

Paris Shows the Way

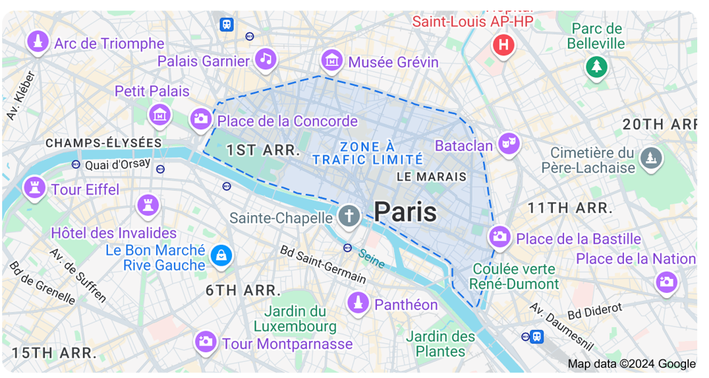

Paris is a city that understands there is no future in keeping cities full of cars because cars destroy vibrancy and activity, pollute the air with fumes and noise, and create danger for pedestrians and cyclists. In acknowledgement of this reality, Mayor Anne Hidalgo recently published a decree that imposes a limited traffic zone (ZTL) in the heart of Paris. It applies to a two square mile area that includes landmarks such as the Louvre and Tuileries Gardens.

Parts of the area within the ZTL like Rue du Rivoli are already pedestrianized and bustling with activity. Paris is full of streets where cars are few and far between, if any, and those are its most beautiful and interesting destinations, beloved by all. It has now decided to expand their example throughout the core.

This decree comes after several years of increasing cycling infrastructure and making Paris a more pedestrian-friendly city, which has been met with international praise. We also consider Paris one of the best examples of a well-designed city in the world and have titled it "a city made for social life."

Paris isn't the only city that has come to the realization that cars destroy much more than they create and so their presence in our cities must be controlled and limited. Amsterdam was going the same car-centric direction as the United States, developing wide, traffic-heavy streets before it decided the benefits of catering to the car didn't justify the consequences. After a slew of car-related deaths, especially of children, the people of Amsterdam pushed back against car culture calling for the end of "child murder" or Kindermoord.

They were successful, and over the past couple of decades, the city has been moving away from cars and towards cycling and pedestrian-oriented infrastructure. It is now considered a haven for non-car mobility and can even be credited for a surge of interest in the urbanist movement.

There are examples like this on multiple continents. Forward-thinking cities around the world are taking measures to move away from cars, with benefits across the board. Having fewer cars in cities leads to more strolling and less driving, more shopping, community connection, social life, and healthier, happier residents. If New York wants to offer its residents the best quality of life it can as other cities are trying to do, it needs to take a step back from its obsession with cars and start focusing on the experience of people living their lives outside of them.

Congestion pricing is one way to do so, but so is the way we shape the streets themselves. Paris is a "city made for social life" and New York can be a "city made for shopping, socializing, community life" or whatever else we want. We just need to design for it.

Related Articles

Who We Are

If you are interested in our helping to build a community-wide campaign or catalytic interventions, presentations, exhibits, and more or supporting the cause contact us.

"There are more and more of us fighting for a different vision of the world—a world that takes care of our most precious resources: the air we breathe, the water we drink and the places we share." – Anne Hidalgo, Mayor of Paris, France