Vibrant cities always need a strong center where people from all walks of life can gather to conduct business, connect with peers, and have fun. With the pandemic rendering many central commercial districts less essential as office hubs, these key places have lost much of the foot traffic and activity that once sustained them. Little sidewalk life and few people visiting businesses, especially outside work hours, leads to an area being in danger of decline. This type of decline is exactly what we are seeing in Midtown, New York City today.

Considering that it's unlikely workers will return to Midtown in the same numbers as before the pandemic, the area needs to adapt by serving a broader function than just providing office space if it wants to survive and thrive. Business districts need to become multi-faceted destinations and social hubs that everyone can use, enjoy and benefit from. But how?

Writing the Next Chapter - Creating a New Heart and Soul for Midtown

We are proposing a plan for a new "heart" of Midtown that supports and augments the recently announced "New" New York Plan.

A new "green zone" can be our approach to Midtown's future, and we think it should start with the connection of two great parks, Bryant Park and Central Park, along 5th Avenue and Avenue of the Americas. This would be the beginning of a loop of dynamic and active destinations. The zone would also connect other areas: Broadway from Herald Square to Columbus Circle and up to Lincoln Center would be part of the broader vision.

Midtown is no stranger to transformation – the area has gone through changes before, including those that revolutionized spaces like Bryant Park, Times Square, and Central Park. The time has come for a second transformation; a post-COVID comeback for Midtown.

Our long history in Midtown is what has led us to do this plan

To know what we can do to help Midtown recover, we first have to look at its past. It is also valuable to look at our past and the work we have done over the past few decades in cities around the world, in order to identify the insights that we can apply to this important project.

The erosion of street life imperils the vitality of downtowns in the post-Covid era

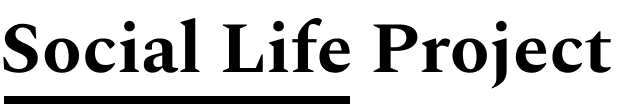

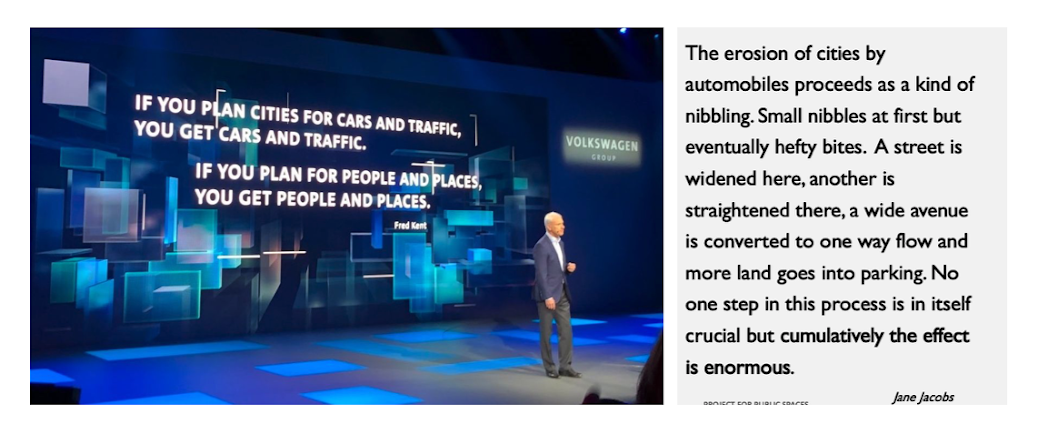

Groundbreaking Research. This part of Manhattan is far different from what it was when we studied two blocks on Lexington Avenue as part of Holly Whyte’s Street Life Project in the 1970s. Our research about how a lively street functions was groundbreaking for the time, giving us a baseline to look at how much Midtown has fundamentally changed over 50 years.

What are some things we learned from our study of Lexington Avenue and 59th Street?

- We observed how a corner food store on 59th and Lexington with a takeout window right on the street narrowed the sidewalk enough to slow traffic and give passers-by a chance to see what was available to eat. This generated business throughout the day.

- We watched the various activities around a single waste basket during the course of a day. For example, we observed how one well-dressed man stuffed his newspaper in the throat of the basket, leaving it sticking out, and shortly after, another man came along and pulled it out, looked at it, then put it back in, and a third well-dressed man did the same after him. A complex dance of daily life that even the simplest of amenities can facilitate. What's more, we noticed how the position of the waste basket next to a lamp pole provided a place to take a break from the heavy fast-paced pedestrian flow.

- We discovered how a small convenience store merchant leased the sidewalk in front of a very narrow store to a vender who sold wigs on a rack. The display of wigs slowed down pedestrians long enough that some decided to pop into his store.

- We analyzed how a bank with a 25-foot blank wall facing the street harms the stores immediately next to it. The owner of a store next door told us that when people walked by the bank they automatically sped up, and it took two or three storefronts for them to get back into a window-shopping pace. He had wisely canted his store window so potential customers would find it easier to see what he was offering, thus somewhat overcoming the harm that the bank's presence did to his store's patronage.

Our Work in Rockefeller Center, Bryant Park, and Times Square

Building on this early work of the Street Life Project, Project for Public Spaces (PPS) was founded in 1975 to apply the lessons learned. For four years our office was in Rockefeller Center where, in return for free rent, we evaluated and did retrofits of public areas around the complex. We also used Midtown as a research/experimental zone, observing public life, coming up with solutions and making interventions to see what impact they would have.

Rockefeller Center

Mayor LaGuardia named Avenue of the Americas, popularly known as Sixth Avenue, in 1945 after its elevated subway was relocated underground. Looking to re-brand the shabby street, he no doubt felt that the new name "Avenue of the Americas" resonated with more grandeur, though it's a name that the avenue has still failed to live up to....perhaps until now.

Rockefeller Center is the heart of this stretch of Avenue of the Americas between Bryant Park (42nd Street) and Central Park (59th Street), but it is clearly the backside of Rockefeller Center. It is two entirely different settings between the original Rockefeller Center, constructed in the 1930s, and the new Rockefeller Center, constructed in the 1960s and 1970s.

In the 1970s, Project for Public Spaces received free office space in return for providing Rockefeller Center with recommendations for improving its public spaces. It became our laboratory, and we worked with marketing and design staff at Rockefeller Center to transform the public spaces within the entire center, one by one.

We added benches along the Channel Garden so people wouldn't sit on the plants, which led to the idea of rotating horticultural displays monthly. We studied ways to remove traffic from Rockefeller Plaza, open up and enliven the underground shopping concourse, activate the area around the skating rink, and control crowds during the holiday. We experimented with different types of benches on Fifth Avenue. Perhaps most notably, we transformed a mid-block plaza called Exxon Mini-park from an area known for drug dealing into one perceived as welcoming. Though the mini-park was sadly the site of sterile and unwelcoming updates a decade or so later, it became a model for what could be done with Bryant Park on a much larger scale.

What Came Next

After doing this work in multiple plazas and public spaces in Rockefeller Center, we took what we learned to Bryant Park, the Port Authority Bus Terminal and later, to Times Square, where we tested out new ways to close Broadway to traffic.

In the 1970’s and 1980’s, PPS used New York City to test strategies for reversing the acute degradation of the public environment that followed the city’s fiscal crisis. This required new strategies to create public-private partnerships around public spaces, with a focus on how to make space safe and usable for all people. Most of the demonstration projects and policy initiatives we undertook in New York have been adopted as dominant practice.

A core activity was also working to transform the way transportation decisions were made in the city, developing analytic methods to study how streets work for all users, promoting transit innovation and user-friendly subways, and the whole concept of short-term testing of street design changes. With its dynamic and varied public spaces, New York is an ideal environment for learning about how great places work, and the lessons that we draw from observing the city's always-evolving parks, squares, and streets inform everything that we do.

Leaping Forward to Today

Now, under the umbrella of the Placemaking Fund, PlacemakingX and The Social Life Project, we work in cities across the globe. The lessons learned during critical early projects, like the revitalization of Bryant Park and Rockefeller Center, continue to serve as a base from which we share placemaking strategies for spaces from Sao Paulo to Singapore.

Using what we learned from our work in New York, we became a global resource, sharing our experiences as placemaking became a way to shape the future of communities around the world, and gathering a wealth of insights and lessons along the way. Now, it's time to come full circle and bring what we have learned from around the world over the past 40 years to Midtown, New York, where it all began.

After bringing all that exposure to what was happening in places around the world, re-examining Midtown was a shock and one that really boggled our minds. So little had changed since we did our work there, 35 years ago. What happened to the area we had spent our early years exploring, studying and helping to create an environment of vibrant social life? What happened to the energy that we helped generate. Can it be brought back?

Current State of Midtown New York City

Today, fast-moving traffic, clogged streets and intersections, and monolithic buildings occupying entire blocks decimate city life, making Midtown Manhattan less desirable as a place to spend time. This becomes increasingly problematic for the area's vitality as even office workers are leaving for other parts of the city or choosing remote work. We must notice the signs of decline and bring life to Midtown's streets before it is too late.

In Midtown's current state, we see wide streets where traffic dominates and sidewalks that are way too narrow, leading to a decline in sidewalk life. What's more, sidewalks have become soulless with bland, boring streetscapes, empty plazas, limited food offerings and an overall lack of interesting destinations.

Plaza Hotel on 59th Street and Avenue of Americas at 57th street

On the left, Lexington Avenue between 58th and 59th Street in 1975. On the right, what we have today.

Central Park 59th Street

There is a noticeable decline in the number and variety of storefronts as big box stores take over entire blocks. And plazas are over-designed – simply there to showcase a building rather than being places where there is true placemaking, active ground floors, and a people-centered design which prioritizes the user's experience. All of these deficiencies make Midtown unpleasant to spend time in. This needs to change.

Plazas along the Avenue of the Americas

Newest Plaza, 5th Avenue and Apple Store - Plaza has no purpose other than an Apple store entrance

With the commercial world spreading away from the city center into what were once fringe centers, and with much of business moving to remote work, areas like Midtown, New York, need to adapt by re-inventing themselves as places that make connections between people just as much as financial transactions. They can no longer be sustained only by office buildings and traffic. It's time to bring the people and soul back to Midtown streets.

Sign up to see our full plan for the "New Midtown

Related Resources and Articles