New Haven has done something remarkable with key streets that, if replicated, can impact communities large and small. Perhaps Manhattan, where crosstown street intersections leave much to be desired, can be the first to follow New Haven's lead.

We have always been laser-focused on streets and how they are either dominated by traffic or supportive of social life and local businesses. It is intersections that offer the most opportunity to change the perception of a street, shifting its role from a vehicle through-way to that of a connector between a socially active set of corners.

In our recently released vision for Midtown Manhattan, we explored the enormous opportunities of Midtown avenues and the major cross-street of 59th Street – all of which could become grand boulevards. Upon looking more closely at the cross-town streets, we began to see something that might well be the most important agenda for Midtown and other business districts and neighborhoods all over the city: The collective impact of the smaller crosstown streets is the biggest issue in Midtown. This is true even beyond well-known Midtown issues like those faced in Columbus Circle, 59th Street and Grand Army Plaza – all of which are stunningly bad at fostering social life. But the cross-town streets are an even bigger problem, because many of the assets that make up those unique streets are the places people would most benefit from knowing about.

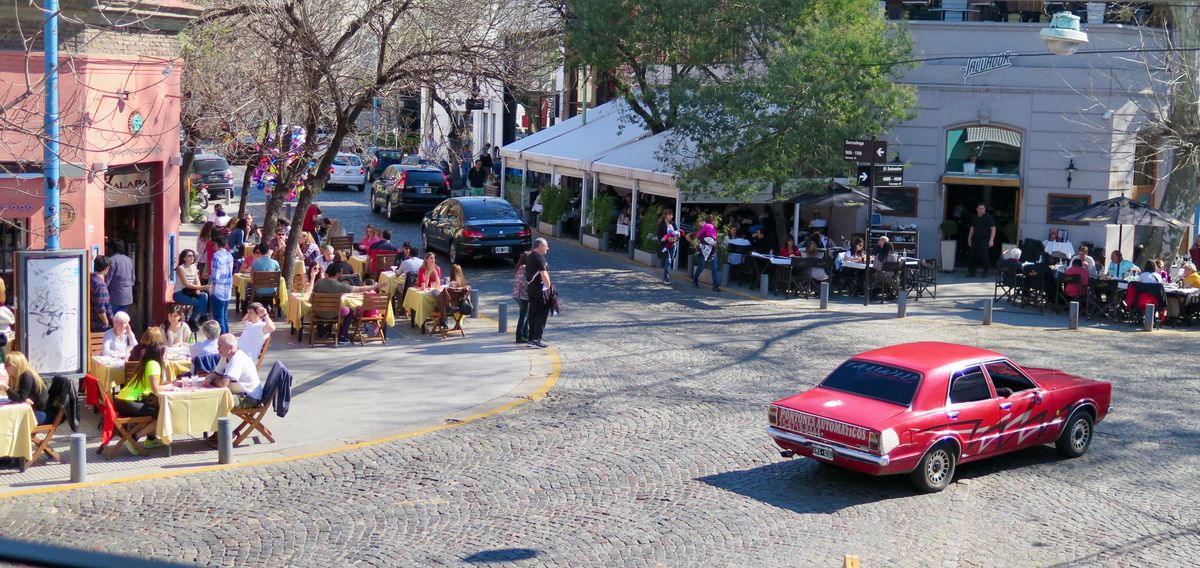

One of the great strengths of New York has always been the special places on small streets adjacent to the major avenues or boulevards, standing in contrast to the nearby stand-alone towers that often occupy an entire block face. We need to create a strategy to rethink intersections to have more human-centered features, such as the kind of vibrant cafés teeming with life in Paris and Barcelona, or the artistic and performative elements found on Calle La Defensa in Buenos Aires, or benches – simple but effective ones such as in Munich, or unique and fascinating ones like in Zurich – all of which serve to activate social life. Revitalizing corners will also involve creating visual gateways into special crosstown street assets, thus having a positive ripple effect for small businesses throughout Midtown.

Car-Centric Midtown Manhattan Cross Streets

Cross-town streets are so full of traffic, especially stacked at corners across Midtown, with the impact being greatest between Lexington Avenue and Broadway from 59th Street down to 14th Street.

Car culture is at its strongest in Midtown. When standing at any of the intersections, there is no sense of what to see or do on the cross-town streets beyond the corner, since cars block any attractions that might be of interest to visitors. The sidewalks are so narrow that any activity, store, or restaurant has no visible presence.

West-bound cross-streets: Narrow sidewalks and three lanes of vehicles.

East-Bound Streets from Avenue of the Americas

Fifth Avenue: 58th Street going East

Fifth Avenue: 54th Street going West

Specifically, these car-centric crosstown streets have been engineered to prioritize the most efficient movement of traffic, often via three car lanes, one being a turning lane with additional green-light time to improve throughput. This has the effect of reducing pedestrian ease of movement and quality of experience at major avenues, and most importantly, it renders side streets and their attractions invisible behind a wall of vehicles.

What is needed to fix this problem is to start with the corner and the entire intersection, and then grow from there, identifying what is offered on each block and then finding ways to highlight it. There also need to be amenities at each corner such as benches, corner restaurants, and "gateway" information to make the area more readable and appealing to visitors.

New Haven

A perfect example of this kind of corner revitalization can be found in New Haven. In what was once a derelict part of downtown, locals have managed to achieve a truly massive change. Initially it was a transformation of one corner on Chapel Street, which then spread to College Street. There, it picked up momentum when the City and Yale University took out one lane of traffic, creating a sidewalk more than twice its original size.

Chapel Street is on the right and College Street is on the left

Precedent for Change

This New Haven intersection, which created a revolutionary transformation in one of the city's main neighborhoods, has emerged as a key example that others can be modeled after. It demonstrates how intersections in cities should be treated as gateways that can also spread to include mid-block attractions, and ultimately entire blocks.

The Story

Around 1980, we were working in New Haven, Connecticut with Joel Schiavone, a progressive Republican who occasionally ran for governor of Connecticut. He owned a large block across from Yale University and had a big vision for the block, including for Claire's Corner Copia which was on a key corner. Our team saw an opportunity to showcase Claire's by expanding the corner where she and her husband had recently started a small but popular vegetarian restaurant.

At that point in time, we were not acting as professionals; we were just noticing simple changes that could be made and how they could impact small businesses in critical locations. We did not know what we "couldn't do." We just did it. Our goal was to give attention to a great small business that was hidden by a wide road going through New Haven between Yale University and our friend's property. Our intervention ended up saving Claire's business and bringing to life the entire block for years to come.

Chapel Street leading up to College Street, where it narrows significantly.

How?

We worked with a retired and highly regarded traffic engineer, Herb Levinson, to narrow the wide Chapel Street into a special district. We asked him what was the narrowest that the lanes there could be and after pushing him on it, we got him down to 9.5 feet. Most streets adhere to highway standards of 11- or 12-foot lanes which is an excessive width for the kind of activity they are meant to support. This simple narrowing gave a strong message to vehicles that it was not a place for driving fast. It was a place where sidewalk life and the pedestrian experience were a priority. This transformed the way-too-wide section of Chapel Street along the New Haven Green from an unpleasant and dangerous throughway into a very walkable "neighborhood Main Street" for Yale University.

This catalytic change kicked off a process that reinvigorated an entire block, already full of potential with its historic properties, but sadly under-used. Mr. Schiavone decided, under our guidance, to keep destinations like Claire's. He also eliminated parking spots and improved sidewalks from Claire's, down Chapel Street, to include museums and the Yale School of Architecture. These changes made Chapel Street into a whole new place to experience, and improved its interface with the university. Meanwhile, Claire's grew in popularity.

We narrowed Chapel Street to create a plaza in front of Claire's Corner Copia. It became a key corner in New Haven after we widened the intersection 25 years ago

Today, Claire's Corner Copia has become a legend and a gateway into Yale University on Chapel Street.

Chapel Street became a vibrant corridor with local retail, museums on the south side, and Yale University on the north side.

It is a story that demonstrates how a "town and gown" activation and a private institution can work together with the City, creating a setting that catalyzes widespread improvements. This is a great example of an approach that can be repeated everywhere, including Midtown, Manhattan.

And then, something amazing happened, starting in 2020

During the Covid years, the entire "block" on College Street become a major downtown hangout, starting with Claire's Corner Copia. As the main destination on a key corner, Claire's was the catalytic transformation that eventually redefined this part of New Haven. Under Yale's leadership, locals have extended the sidewalk using paint and bollards, taking back a whole lane from traffic and adding cafes not only on the sidewalk but also in the former parking lane.

What was a major egress road out of New Haven was narrowed down to one lane and in a rare and beautiful moment, sidewalk life and the pedestrian experience were prioritized over the flow of traffic. What happened here during Covid was an extraordinary revolution for social life and community revitalization, and considering how cheap and easy it was to implement, other places can and should follow suit.

Other improvements on the block

Within the block, the impact also happened with parking; the buildings on Chapel Street are active where they front the street and in the back where the parking is.

The awe-inspiring impact of this corner transformation is not a New Haven specific phenomenon nor one that can only work in small towns. Communities big and small have main streets and cross-streets, sidewalks and corners. And people everywhere behave in much the same way; they avoid cars and are drawn to social life. Therefore, the intervention we applied in New Haven can and would be successful in reinvigorating social and economic life in places at all scales. Midtown will benefit from such an intervention, as would anywhere else. When you design for cars, you get more cars at the expense of everything else that gets eaten away to make room for them. But when you design for people and businesses, you create places and communities that thrive. It all starts with the corner.

With that in mind, we will soon be launching a global campaign titled "Put a Bench on Every Corner," where we will encourage communities to see that something as simple as a bench can serve as a catalytic seed for widespread change in how we approach streets and sidewalk life. Sign up to our newsletter for updates on the campaign, and read further about the concept behind it here.

Takeaways

A simple yet catalytic change on a key corner creates a chain reaction of exemplary improvements over time, i.e. growing from the center.

Starting with a highly visible local example like Claire's Corner Copia leads next-door merchants and restaurants to get involved, creating a ripple effect that spreads down the block from the corner. Each business becomes part of a local improvisation effort that leads to small hubs where collections of businesses help each other.

In other words, LQC (Lighter, Quicker, Cheaper) works: Something as simple as paint can turn a street around. Transformative change doesn't have to be expensive or complicated.

Related Articles

The Foundation and Future of the Placemaking Movement